March 24,2025

We drove south to leave the winter of Ottawa, even though we enjoy snowshoeing. Escaping springtime offers a welcome reprieve from the winter’s cold and snow. Despite my pollen allergies (managed by Claritin), late March in the Carolinas offers ideal cycling weather.

Driving south towards Beaufort, South Carolina, I sighed in relief at leaving the crowded, monotonous, and speedy Interstate 95 behind. Driving for hours had numbed my feet, so I hoped for less, slower traffic on Route 21 East. Although slower, the traffic picked up closer to Beaufort on a four-lane highway.

The expansion of military bases (Parris Island and Beaufort), resort construction (Hilton Head Island), and a Northern retiree influx have driven development along South Carolina’s east coast.

We learned from a hotel employee at check-in that Beaufort’s population has almost doubled since the pandemic, nearing 15,000. It is not only retirees but also people working remotely who have arrived to take advantage of lower housing and living costs.

When Kathy stayed here thirty years ago, she stayed in one of the huge antebellum houses on the waterfront, used as a B&B in those days. Today, developers meticulously redeveloped the waterfront, and they restored the antebellum homes along the waterfront to their original designs. The city designated the downtown area a historic district, and we enjoyed a quiet walk admiring the architecture.

Cycling the Spanish Moss Trail from Beaufort to Port Royal was a smooth ride (it follows the old Magnolia rail line). The paved, twelve-foot-wide trail was flat, crossing marshes with many boardwalks and with the temperature in the mid-twenties (in the seventies in Fahrenheit), was ideal for a bike ride. Much of the Trail crossed areas with oak trees from which Spanish moss hung. I assume the source of the name for the Trail. Although the hanging moss is attractive, avoid touching it because it might contain chiggers.

The paved trail was great for riding, but I knew that falling off the bike would be rough, experiencing injury if going at the maximum allowed speed of 15 mph.

We sped through the twelve-mile trail, pausing to talk with people going in the opposite direction. We avoided talking about politics. We did not know how local people would react to talking to us Canadians, in view of Trump’s desire to annex Canada.

I noticed different organizations took responsibility for maintaining sections of the trail, which included benches at viewing sites, including the military that were in abundance in the area.

In less than a couple of hours, we arrived at Port Royal, at the other end of the trail. We were ready for a cup of coffee and found in the center of Port Royal a home converted to a restaurant with a name Corner Perk that offered fancy coffees. Their muffins were so special we couldn’t resist.

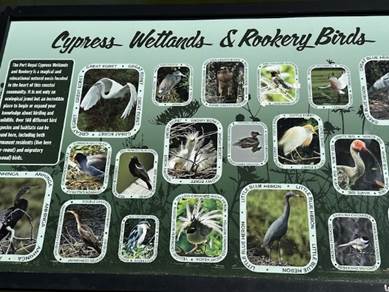

Next, we saw a sign for the Cyprus Wetlands rookery, home to hundreds of local birds (egrets, cormorants, bats, herons, etc.), right by the coffee shop. A boardwalk crosses a lake, going by an island with small trees that provide nesting grounds for birds. We noticed many turtles and alligators also slept on the shore of the island.

Returning to Port Royal, we found a small house converted to a restaurant boasting a sign for Griddle and Grits and the menu included grits with shrimp, with chorizo and grits with different ingredients. I like spicy foods and chose chorizo on grits, which turned out to be excellent. Kathy chose she crab soup, which also turned out to be a good choice.

On the return journey, we paused on a bench and were approached by a man who looked like a bear of an angler, who sat down, smoked a cigarette and started a conversation. He wanted to know all about us and then described his entire life story, including where he was born, where his family members were born and all the ailments they each had. I gathered he has been a floater with jobs in many states before settling in Beaufort. We could not resist listening to him; overall, it was an enjoyable social engagement.

We stopped at a Publix grocery store on the way home to pick up dinner. The Spanish Moss Trail is a nice, paved trail, but it was a bit too tame for us. We like longer and wilder trails with fewer refinements.