December 4, 2022

St. Judas Thaddeus Church in Sopron, Hungary

I have never been a church-going person except in my youth when my father, who went to a Jesuit school, made us go to church on holy days like Xmas and Easter.

My memory of going to the old baroque church in Sopron, Hungary – St. Judas Thaddeus, built by the Dominicans in 1715 – is not pleasant (see picture on left). The huge nave of the church was a forbidding, gloomy space for a small kid. It was cold inside with a stone floor.

Nobody received us at the entrance lobby; nobody led us inside. I stood for the service at the back of the church, listening to the sermon; that gave me a quick getaway if I got too cold or bored by the service.

The sermon and the entire mass were in Latin, which I could not understand. (The Catholic Church required that Mass be carried out in Latin until the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965, which permitted the use of the vernacular.)

And the priest dressed in ecclesiastical clothing for delivering the sermon, giving him – and it was always a “him” – a formal appearance, talking down to us from the pulpit ten feet above us.

And, of course, we had the confessionals in little cubicles on the side of the nave of the church, where it was dark and I had to kneel in front of a wire screen behind which was the priest listening to your sins which were related to disobeying your parents and swearing using religious imagery.

The salvation for my “mortal” sins, prescribed by the priest, was always saying a prayer fifty times or more, depending on the gravity and length of the list of my sins. I always thought the confessional was a good bargain to repent your “mortal” sins; it never took longer than a half hour to get back on the good side of the Lord.

Once I repented my sins, I lined up for communion wafers, the “sacramental bread”, that tasted good. Then we were free to leave the church.

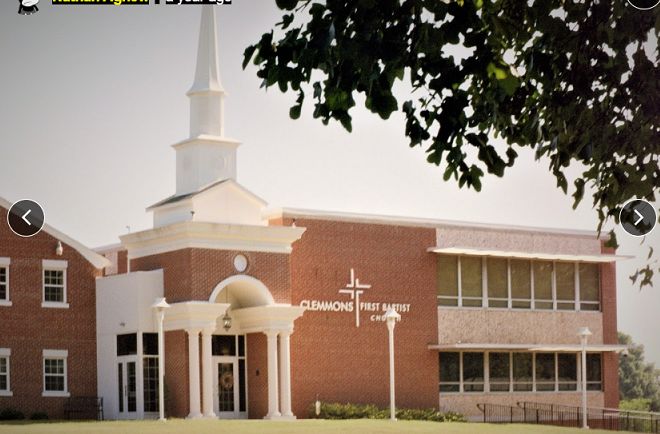

Clemmons First Baptist Church, Clemmons, North Carolina

I encountered a huge contrast to my experience with my baroque church when we visited our family at the end of November in Winston-Salem NC, and joined them for Sunday service at Clemmons First Baptist Church (see picture on left), on the last Sunday of the month, the beginning of Advent.

We entered the modern building with a red-brick façade, where smiling people welcomed us into the well-lighted and comfortable lobby and ushered us into the nave of the church to padded pews.

I felt like I was in a large living room entering the lobby and once we sat down, lively conversation filled the church until the service started. The Pastor welcomed the attending children, and the organist played hymns with the text shown on two gigantic video screens over the stage so that we did not have to pick up the hymn books to follow the songs.

All the people were informally dressed. The Pastor showed up in slacks and a sweater and gave a sermon from notes, speaking freely most of the time.

The Pastor addressed the meaning of Advent by asking us to look at our state in life to make sure we are ready for the second coming of Jesus. He illustrated his point by talking about himself getting old, although he said he is 44 years old; to me, he is a young man. But he said he feels his age when getting up “from a toilet seat”, eliciting laughter from the audience. He added that now one can install higher toilet seats to help with that. This type of informal sermonizing made me feel quite comfortable.

Then the Pastor, in a more serious vein, talked about embracing silence, meditation, and the healing power of nature. I felt quite at home by now: we just came from the New River National Park in West Virginia, where we spent a few days hiking and enjoying nature in silence.

He said there is no need to push yourself to get ready for the second coming by reading the scriptures. Instead, he said, wait until the desire to do so comes from within yourself. I liked his low-key approach to religion; embrace religion when you are ready for it. I was ready to join the church!

At the end of the worship, we followed the Pastor, who walked into the lobby to welcome the audience. I told him how much I enjoyed his sermon, shaking hands with him.

I noticed a board in the lobby with pictures of a dozen deacons (members of the church); I learned that all the families frequenting this church have a deacon who follows their well-being and provides help when needed. For example, should someone get sick and not be able to cook, the deacon would organize members of the church to bring over food. My brother-in-law is a deacon here. I thought the deacons performed an important and valuable role.

If we had had churches like the Clemmons First Baptist Church when I was growing up, I may have been a lifelong churchgoer.