March 9, 2025

Rat Temple and Local Fair

Traveling in India never ceased to surprise us with its diversity in languages, food, and beliefs rooted in thousands of years of history and customs. One example of a remarkable story and a highlight of our journey was visiting the Rat Temple in Bikaner. In this temple, rats are considered holy and revered.

The origin of the Rat Temple dates back to the fourteenth century. According to legend, the Goddess Karni Mata lost her youngest son, Lakhan, who drowned. In her grief, the Goddess commanded Yama, the god of death, to bring Lakhan back to life. Yama, however, explained that he could not do so but that Karni Mata (an incarnation of Durga, the Goddess of war, power, and protection) could restore her son’s life. Karni Mata decreed that her family would be reincarnated as rats.

Today, around six hundred families claim to be descendants of Karni Mata. These descendants maintain the temple, clean up after the rats, and prepare food for them, often sharing meals in their presence.

To enter the temple and enjoy the experience of 20,000 black rats running freely, you must be barefoot, as some rats may even scurry over your feet. Upon entering, we removed our shoes and felt the rats scampering across our toes. This experience is certainly not for the faint-hearted! A deep sense of emotion ripples through the worshippers when they spot an albino rat, which is believed to bring good luck. Kathy spoke with several visitors who had made the trip, hoping to see a white rat to enhance their fortune. Unfortunately, on the day we visited, we didn’t see an albino rat or anyone else. We stepped outside the temple for refreshments and regained our sense of reality.

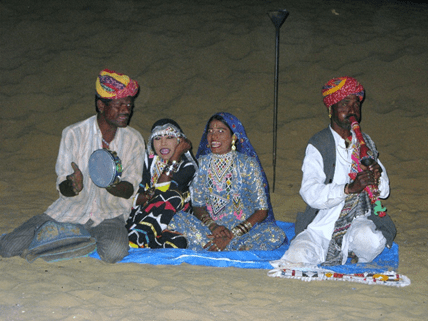

Our next stop left a deep impression on me. Our guide, Shyaam, took us to a local festival with arts and crafts, Rajasthani foods, and entertainment. Although the festival’s nature was familiar and similar to North America’s, the begging scene that enveloped us shocked me. Beggars were prevalent, and Westerners present were their primary focus.

The most grotesque and upsetting memory that I have is of a skinny, undernourished boy of maybe ten years of age who had only one leg and was running after me on his two hands and his one leg like a spider, reaching with one hand to me begging for anything. I was unable to escape him. His tenacity forced me to leave the venue and go to the parking lot before he would leave me alone. He chased me from the festival!

I felt sick to my stomach and dispirited to see this deformed beggar. I read about the maiming of children by the begging mafia in India who steal children and maim them to make them more profitable in begging, but seeing one was awful. It was the most disturbing experience that I had in India. Although I read Rohinton Mistry’s Fine Balance and we had gone to see the Slumdog Millionaire film before we went to India, seeing the slums and the beggar children in real-time was shocking. Seeing this poor, deprived child made me think about the unfortunate circumstances that led to his life in begging.

Still, I knew that despite being a tough moral choice, giving to beggars inevitably meant being swarmed, overwhelmed, and in danger of physical harm in such crowded situations (we had such experience in Asia).

When driving, Shyaam delighted us with his discussion of the unique aspects of Indian culture. On our drives, he explained to us the caste system of India, which he was proud of. He was a Singh, implying the second highest caste: the warriors and rulers. Military service ran in his family. Caste, we learned, does not guarantee wealth or even education, but it imparts status. Shyaam was a tour guide and lived a modest life. He explained Brahmins were priests and teachers, comprising the highest caste. Next to the warriors were the farmers, traders, and merchants, followed by the laborers. The Dalits were outcasts, the street sweepers (and not part of the caste system).

Interestingly, India’s history includes a prime minister who was a Dalit, and many merchant classes have become quite wealthy. I was initially unsure about the meaning of the caste system, especially since individuals from various backgrounds could become prime ministers or pursue higher education, leading to what we might describe as an upper-class lifestyle filled with money and possessions. We observed that the caste system was more apparent in the North of India, where there are more Hindus, compared to Chennai or Tamil Nadu, which has a more diverse population that includes non-Hindus.

We had an interesting discussion with our guide about ultrasounds for pregnant women, which Shyaam explained can be dangerous for women. I was about to debate with him when Kathy quietly suggested that I stay silent on the topic. I understood that in India, there is a preference for boys because they provide support to the older generations, benefit from a dowry when they marry, and light their parents’ funeral pyres. Having a boy ensures that the family name continues.

I’ve read that there is a worsening gender imbalance in India. In 1994, a law was passed to address this issue; the law discourages prenatal sex determination, monitors these procedures, and prevents the gender imbalance that could lead to a shortage of women for marriageable men. The murder of baby girls has become an ethical concern in India, according to articles I’ve come across