March 7, 2025

During our journey from Jaisalmer to Udaipur in Rajasthan, India, we stopped to visit a Jain temple in Ranakpur. After a long walk, we arrived at the temple’s entrance. Upon entry, the building’s dress code mandated covered knees and shoulders. Despite the temperature being in the upper 30s Celsius outside, the dress code prohibited sleeveless shirts. Fortunately, we were well-prepared to meet this requirement since we always wore long-sleeved shirts and pants while traveling.

Temple entry required removing all leather items, such as wallets and belts. Jain temples prohibit leather because producing it involves killing animals, directly contradicting the core Jain principle of “Ahimsa,” or non-violence. The temple provided lockers for visitors to store their items, and we had to improvise to keep our pants up after removing our belts.

At the entrance, we saw a sign advising women not to visit the temple while menstruating. This caught my attention, so I decided to research the source of this custom online. A social media comment explained, “In India, people are not allowed to visit a temple unbathed or in dirty or unwashed clothes.” Similarly, temple authorities prohibit any bleeding man or woman from entering, to maintain the temple’s purity and hygiene.

People have practiced Jainism, an ancient religion with more than five million followers for over five thousand years. It is based on the principle of peaceful coexistence and offers guidelines for living harmoniously with others. I was ready to become a follower. Unlike many other religions, Jainism does not worship a God; its followers revere the Tirthankaras. Jainism admires the 24 Tirthankaras—enlightened teachers or saints—for their teachings and wisdom, but does not worship them. They have achieved liberation from the endless cycle of birth and death.

A vegetarian diet is essential for all Jains, reflecting the core principle of non-violence or non-injury. Jains are very conscientious about their food choices. For example, they avoid root vegetables, such as potatoes, because harvesting them results in the death of the entire plant. Many Jains also operate animal shelters throughout India, showcasing their commitment to this principle.

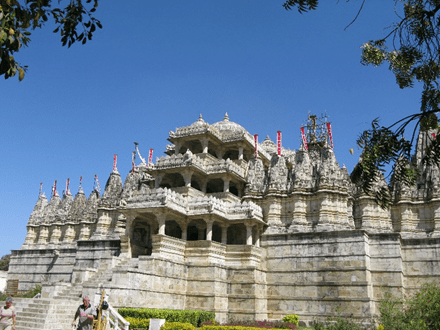

We learned that the Ranakpur Temple is one of the largest and most significant temples in Jain culture, recognized as one of the five most sacred sites for Jains. Remarkably, a dream inspired Darna Shah, a local Jain businessman, to build the temple in the fifteenth century. Of the renowned artists and sculptors he invited to submit designs for the temple, architect Deepak presented a plan that profoundly impressed Darna. Deepak promised to create a temple based on Darna’s vision. The king of the province provided land for the temple and suggested building a town near the temple, which has become Ranakpur.

The temple covers an area of nearly 48,000 square feet. It includes 29 halls and 80 domes, all supported by 1,444 intricately carved marble pillars, each uniquely designed. Four distinct doorways lead into its chambers. These chambers ultimately guide visitors to the main hall, where the statue of Adinath, the first spiritual leader of the Jains, is located. Remarkably, you will arrive in the central courtyard regardless of which of the four entranceways you choose.

The temple’s architecture is so well-designed that artificial lighting is unnecessary; natural sunlight illuminates the entire building. Construction began in 1389 and finished in 1458. The numerous openings and high ceilings kept the air inside significantly cooler than the scorching temperatures outside during our visit.